Postmortem Diffusion of Alcohol and Trauma

Postmortem diffusion of alcohol from the stomach into the surrounding blood and tissues can occur and is another possible source of falsely elevated postmortem BACs. Diffusion should be suspected if:

Stomach alcohol concentration >>> BAC > Urine alcohol concentration

A laboratory scientist, forensic or medical examiner. Focus to hand and swab.

This would indicate that the victim died in the absorption phase of the BAC curve and so the stomach alcohol concentration would be expected to be higher than in victims who died on the declining phase of the BAC curve (WOA70302). A higher stomach alcohol concentration would provide a greater alcohol concentration gradient and a potentially greater risk of the diffusion of alcohol into the surrounding tissues especially the heart. To greatly reduce the possibility of postmortem diffusion from the stomach, samples from the periphery such as blood from the major leg (iliac) vein or vitreous humor are usually collected (if available).

Plueckhahn Redux

The Australian pathologist V.D. Plueckhahn, in addition to researching the effects of putrefaction on postmortem BAC as seen in my previous blog, also studied the effects of diffusion of alcohol from the stomach. He measured the stomach alcohol concentration of 230 postmortem cases and found the highest to be approximately 3% and concluded that people do not usually die with a “bellyful of liquor” (WOA70301).

He next instilled between 250 mL of 10% v/v alcohol to 500 mL of 25% v/v alcohol into the stomach of 20 cadavers and measured blood from the leg vein, right and left side of the heart and found no significant diffusion into these blood samples, if the chambers of the heart were intact.

Diffusion by Aspiration of Gastric Contents

With that said, postmortem diffusion can occur by another route in addition to diffusion from the stomach. If the deceased regurgitates alcohol-containing gastric contents shortly before death or if aspiration occurs postmortem when the gastric sphincter relaxes concurrent with the onset of rigor mortis, alcohol can then diffuse via the airways towards the pulmonary vein and thus to the left side of the heart.

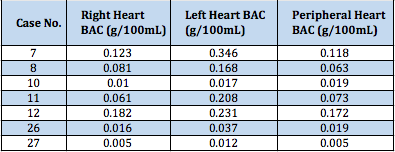

In an excellent study by Pelissier-Alicot et al in 2006 (WOA70304), the alcohol concentration of the right cardiac blood, left cardiac blood, peripheral blood, urine, vitreous humor and stomach contents were measured in 30 postmortem cases. The following Table shows the alcohol concentration of the right heart, left heart and peripheral blood in seven cases with the autopsy findings of regurgitation of stomach contents.

n cases of aspiration of gastric contents, the right heart BAC is a much more reliable sample than the left heart. The right heart blood glucose concentration, however, is much higher than the left heart blood glucose concentration making it more susceptible to postmortem putrefaction. Plueckhahn found that the mean right heart blood concentration was 201 mg/100mL compared to 62 mg/100mL for the left heart blood. This was probably due to agonal glucose production (glucogenolysis) in the liver which diffused into the right chamber of the heart (WOA70201).

Why Not Always Peripheral Blood?

Since heart blood may be affected by postmortem alcohol diffusion which does not occur in peripheral (arm or leg vein) blood, why not just determine the peripheral BAC? There are several potential problems with only relying on peripheral blood.

Heart blood represents the central blood alcohol concentration, the BAC that is affecting the brain and, in cases of fatal alcohol poisoning, the peripheral BAC may be much lower. In one case an 87 year old man consumed 1L of whiskey over two hours. Fifteen minutes after the end of drinking he was seen snoring loudly in bed. Two hours later he was found dead. An autopsy was conducted the next day with the following results:

Femoral BAC = 0.152 g/100mL

UAC = 0.077 g/100mL

Pulmonary vein BAC = 0.316 g/100mL

The authors conclude that if they had relied on the femoral BAC alone, the cause of death would have been a “heart attack”, rather than acute fatal alcohol poisoning (WOA70407).

Peripheral blood and vitreous humor alcohol concentrations can also be affected by extreme environmental conditions to a greater degree than the more protected heart or central blood. Fire can lower the peripheral BAC (WOA702U2). Vitreous humor alcohol concentrations can also be lowered in bodies found in water (WOA70606). Vitreous humor alcohol concentrations also tend to lag behind the BAC and the VHAC: femoral BAC ratio has been found to vary between 0.63 to 1.75:1 (WOA70605). Urine alcohol concentrations also lag behind the BAC and although tend to be more stable than blood also can have falsely elevated alcohol concentrations due to putrefaction (WOA70702).

Trauma

On the morning of April 19th 1989 the USS Iowa was undergoing a gunnery exercise and at 9:55 a.m. an explosion occurred in the Number 2 turret killing 47 of the crew (WOA70214). Autopsies were begun within 48 hours after death. Of the 47 victims, 23 (49%) had a positive BAC, of up to 0.190 g/100mL. In my previous blog, I cited Plueckhahn who stated that

“High blood alcohol levels may develop during putrefaction and levels up to 0.200% do not necessarily indicate that alcohol was imbibed before death” (WOA70202).

Analysis of other tissues for alcohol and good postmortem alcohol interpretation found that the BACs were all due to putrefaction and, therefore, alcohol intoxication could be ruled out as a cause of this tragedy.

Explosions and crushing deaths can liberate the micro-organisms in the gut and spread them more widely and rapidly than non-traumatic deaths resulting in a greater and earlier risk of falsely elevated BACs. Also in these deaths, the stomach and the heart may be ruptured causing a rapid and complete postmortem alcohol diffusion.

Interestingly, in stabbing and gunshot wounds to the chest, there appears generally to be little postmortem diffusion of alcohol from the stomach to the heart. However, in eight cases in which there were lacerations of the heart, liver, stomach and esophagus, which occurred mainly in fatal motor vehicle collisions, elevated heart BACs of up to 0.891 g/100mL were detected which were probably due to postmortem diffusion (WOA70305).

Conclusions

Postmortem alcohol toxicology is a fascinating and complex area of forensic alcohol toxicology. There are no absolute rules which will apply for all circumstances. Each case must be individually evaluated to obtain the proper alcohol interpretation. The samples which should be analysed for alcohol should include the right, left and cardiac blood, urine and vitreous humor.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Burr Hartman, Anjum Choudhary, Stephen Morley, D’Michelle P. DuPre, Dennis Kitainik and many others who provided useful and interesting comments to the posting of the first postmortem blog on LinkedIn. Your comments provide excellent input to my blog and I invite all of you to share your thoughts w ith me here on my blog or via LinkedIn.